“I don’t think I’ve ever had a consistent style from film to film. But one of the things I’ve always believed is that filmmakers need to tell their own stories — and also, that the people who are involved in those stories should tell their own stories.”

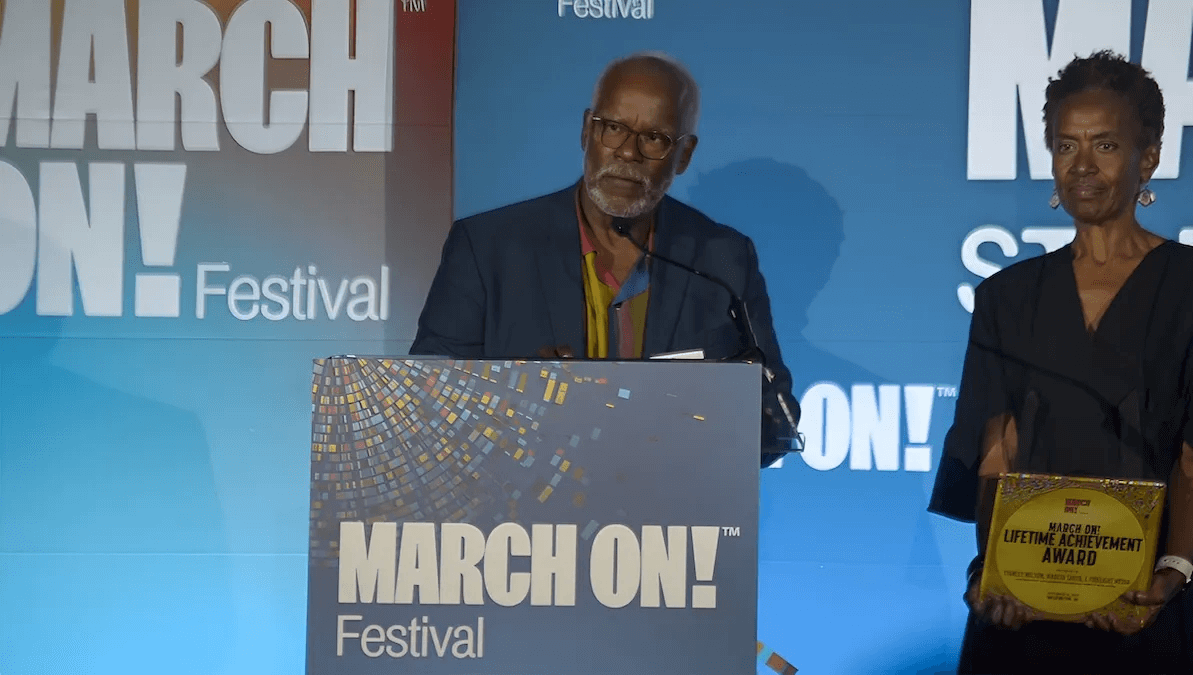

Responding to a question about his filmmaking style from NPR’s Eric Deggans during their keynote conversation yesterday at Realscreen‘s virtual summit, RSS Lite, renowned documentarian Stanley Nelson — this year’s recipient of the Realscreen Legacy Award — instead turned his lens toward the stories he has sought to tell rather than himself. One of the primary filmic chroniclers of the African American experience, Nelson has amassed more than two dozen directorial credits and numerous honors over the course of his 30-plus year career, including most recently an Oscar nomination for best documentary feature for his latest film, Attica, which he co-directed with Traci A. Curry.

Beyond his own achievements, Nelson has also helped launch dozens of other films (and careers) through the Documentary Lab, which he and his wife and partner Marcia Smith established in 2009 through their company Firelight Media. During his keynote, Nelson elaborated on the principles that gave birth to the Lab, most notably his conviction about the importance of cultures chronicling themselves from within.

“I always think of it as, if a story is an ocean, then someone who’s coming from outside the culture, they can swim on the top of the water, but they can’t dive deep — they can’t dive down to the bottom, because they haven’t grown up in that culture,” he said.

Nelson illustrated this idea with a vivid description of a sequence from his 2015 film Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution. “One of the last things that happens in the film is the Panthers are in a shootout with the L.A. police, and they’re trapped in their headquarters — they’re all shot up, they’re running out of bullets so they can’t fire back, and the police are about to break down the doors.

“We were interviewing two of the guys who were there, and I asked one of them, ‘So you’re in that situation, how did you feel?’ And he looked me in my eye and said, ‘I felt great. I was a Black man making my own rules.’

“And he’s looking me in the eye, and what he’s saying to me is, ‘You know what I mean?’ And I knew what he meant, and he knew I knew it. He didn’t have to say, ‘After 200 years of oppression, and after going through slavery…’ — just, ‘I felt great.’ That’s part of what you can bring to a film if it’s about you and about your culture.”

As Nelson explained it, the Documentary Lab was begun to revive a dormant tradition that had first emerged during the same period of political and cultural ferment he had chronicled in Black Panthers. “When I was coming up years ago — we’re talking about the early ’70s —the Panthers were out, and the Young Lords, and it was a time of revolution and change. And people were like, wait a minute, there’s no Latinos, there’s no Black folks [in the film industry]. So there were some programs [started] to help people of color get into the business. And all of those have pretty much disappeared.”

In response to this felt need, Nelson and Smith launched the Firelight Documentary Lab, which every year welcomes 10 to 15 early-career non-fiction filmmakers for an 18-month mentoring and project development program. As Nelson noted, the Lab has not only helped grow the corps of documentary directors of color, but also increased representation throughout the other ranks of the industry.

“When [the Lab participants] make their first film, they’re [often also] hiring associate producers who are of color, editors of color, et cetera,” he observed. “And now [those people] have a credit, and then they can go on [to develop their own careers in the industry].

“So hopefully, slowly but surely, we’re changing the look and the makeup of the industry. It’s not an explosion,” he laughed, “but it’s one little tiny step at a time.”